Optimal automation of ordering processes in retail: a key to success

How a medium-sized company in Austria masters the challenges of modern ordering processes

by Dominik Falkner, MSc

In the modern world of retail, the efficiency of order processing is at the heart of a company’s success. In view of the rapid development of online retailing and rising customer expectations, it is more important than ever for retail companies to establish a smooth and effective ordering system. This article is dedicated to the challenges faced by a medium-sized retail company in Austria, which is exemplary for many companies in Europe. This company operates around 165 stores and sells its products both online and in physical stores, with each store offering specialized products tailored to the needs of the respective country.

Contents

- The importance of efficient order processing in the digital age

- Challenges in retail order processing

- Ordering suggestions: Heuristic methods for avoiding stock shortages

- Focusing on the customer: using models and evaluating the product portfolio

- Silent mail: Interaction between the components

- Conclusion: Over 50% effectiveness – automated order proposals transform the supply chain

- References

- Author

The importance of efficient order processing in the digital age

Order processing, especially in such a diversified network, is a complex challenge. Until now, the ordering process for stores and the central warehouse required extensive specialist knowledge and a lot of time, as orders had to be created manually. This task is complicated by the need to minimize costs per supplier, maintain optimal stock levels and ensure that products are reordered on time. The importance of an efficient ordering system is underlined by studies that show that customers switch to the competition if products are not available, which can lead to declining customer loyalty and dissatisfaction in the long term.

Challenges in retail order processing

This article focuses on a retail company in Austria that shares characteristics with other medium-sized retailers. The company operates around 165 stores in Europe and offers its products online and in stores. Each store sells special products, with the product range being tailored to the respective country. Some products are shared by the stores and ordered in larger quantities from a central warehouse. Until now, stores and the central warehouse have had to order products manually. Creating orders requires a lot of expertise and time. This is compounded by the need to minimize costs per supplier, maintain good stock levels and ensure that products are ordered on time when required. Getting to grips with the problem is particularly important for online retailers because, according to a study by Dadzie and Winston [2], many customers will buy a product from a competitor if it is not available. Anand and Chadha [3] point to long-term negative effects such as declining customer loyalty and dissatisfaction with substitute products. Zinn and Liu [4] also show that stock shortages can damage a store’s image.

The main objective of this project is to improve this process and support it by calculating order proposals per supplier. This is done by combining business rules (per supplier and warehouse) with a system that estimates demand based on historical data and related events. Aastrup and Kotzab [1] provide an overview of the current possibilities for tackling this problem.

Below is a strategy that aims to ensure that the right amount of stock is available by forecasting customer demand.

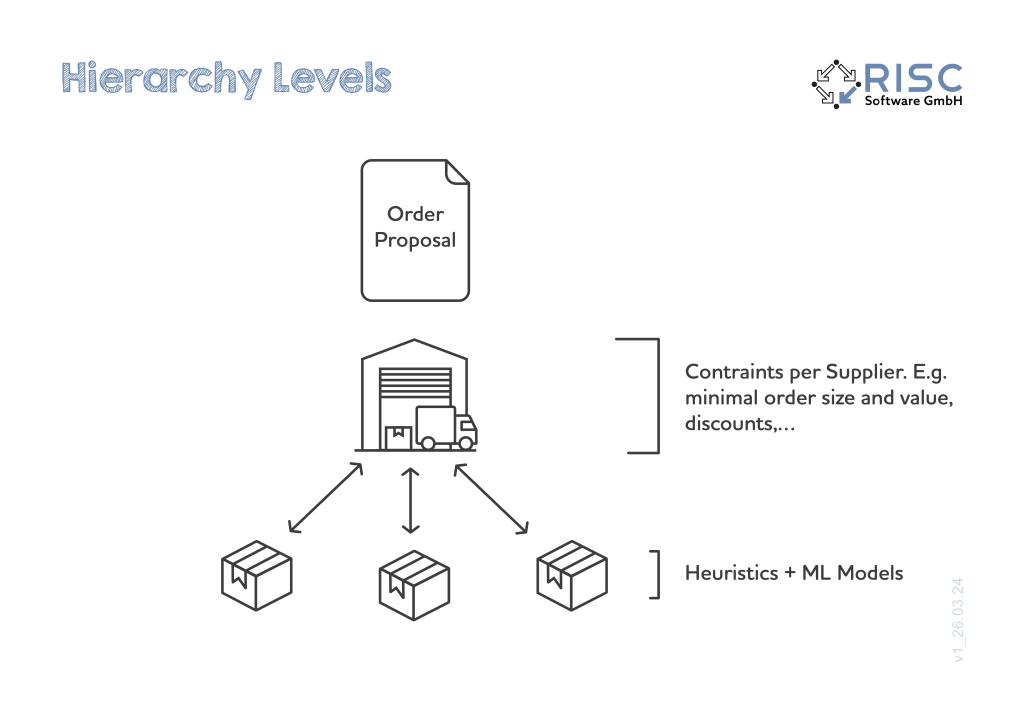

In order to accomplish this task, all suppliers are regularly taken into consideration. Each supplier delivers a certain number of products, and the key question is which products need to be reordered. At the lowest level, heuristics and forecasts are used to determine the time at which a product is likely to be out of stock. Based on this assessment, a preliminary requirement is determined, which leads to the creation of a “shopping basket” for the respective supplier. This shopping cart can then be customized using specific rules. For example, some suppliers require a minimum order quantity or certain order units (e.g. pallets instead of boxes). Here, too, attempts are made to achieve discounts by possibly ordering more than is necessary. Next, the procedure at the lowest level is explained in more detail.

Heuristics are methods for finding solutions to problems quickly and with practical means. People often rely on simple rules or experience instead of analyzing everything down to the smallest detail. They help to make quick decisions when there is no perfect solution.

Figure 1: The different hierarchical levels of the procedure. The system generates an order proposal based on a supplier. All products per supplier are considered for this purpose. Demand is estimated for each product using heuristics and forecasts.

Ordering suggestions: Heuristic methods for avoiding stock shortages

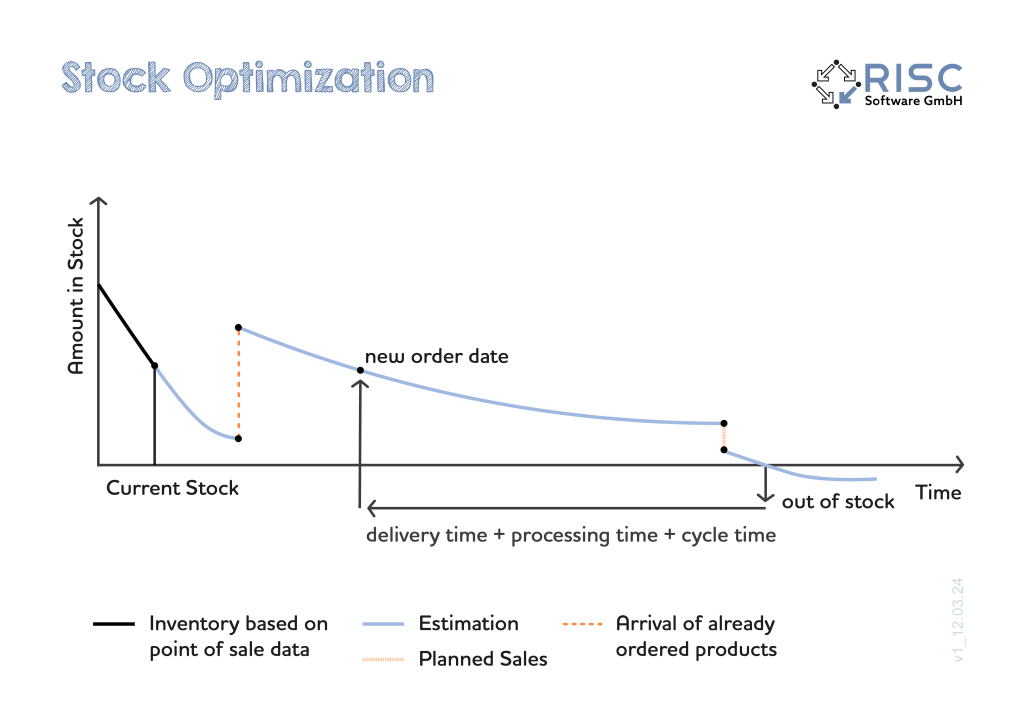

To ensure efficient and cost-effective ordering, various factors must be taken into account when creating order proposals. Firstly, sufficient stock should be available to meet future demand in order to avoid stock shortages or delays. A heuristic was used for this purpose, which is shown in Figure 2. The idea is to ensure that the ordered goods are available before the stock runs out, this point is marked in Figure 2 by the “out of stock”. This point in time is determined on the basis of historical data, which is merged with the demand estimate provided by the forecast component and all known orders and sales in the future. To ensure that the order arrives on time, a time window is constructed backwards to determine when the product must be ordered. The time slot consists of:

- Delivery time: The time it usually takes to deliver the goods, including supplier-specific processing times.

- Processing time: The time that elapses before the goods are available for sale. This includes sorting, unpacking, etc.

- Cycle time: The time between two orders. This is a parameter that indirectly controls how often a product should be ordered.

Additional factors are also taken into account, such as minimum order quantity, discounts and minimum order size. Overall, we are looking for ways to keep the costs of the order low, but in consideration of discounts. Price tables are also included in order to order the products at the best possible conditions and in appropriate quantities and units. To make the system adaptable, individual rules, such as safety stocks, can be defined for each product and each supplier.

Figure 2: Predictions of machine learning models that are integrated into the heuristics. The black line shows the current stock level. The red and green dashed lines show planned sales and purchases respectively.

Forecasts (blue line) are used to estimate when the warehouse would be empty. At this point, a time window is constructed backwards to determine when the product needs to be reordered.

Focusing on the customer: using models and evaluating the product portfolio

During training, both simple and robust methods are evaluated and more complex models are trained. The latter take into account additional information such as the day of the week and upcoming public holidays. The system uses LightGBM [5] and simple statistical models (average, moving average,… ) to train and compare different models for time series forecasting. LightGBM was one of the most frequently used models in the M5 forecast competition [6]. Another interesting point is dealing with a changing product portfolio. Products that are no longer sold are filtered out before training begins. For new products for which no historical data is available, purely statistical models are used, which generally work well with limited amounts of data. To deal with replaced products, a model is provided with the old product data in addition to the new data.

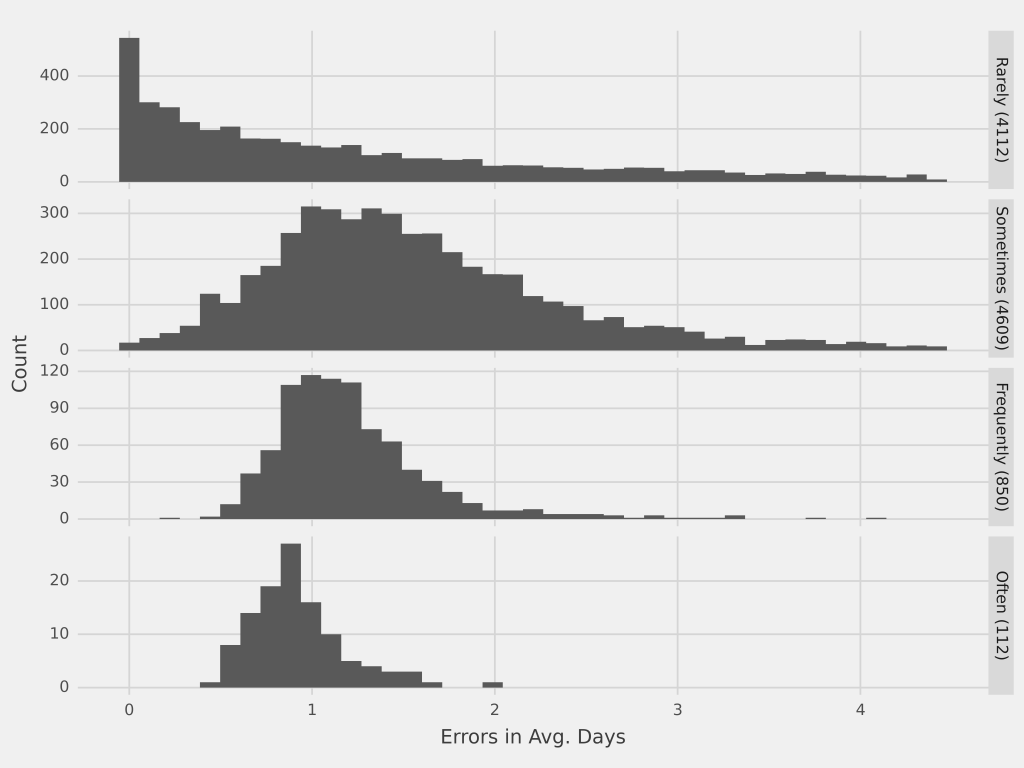

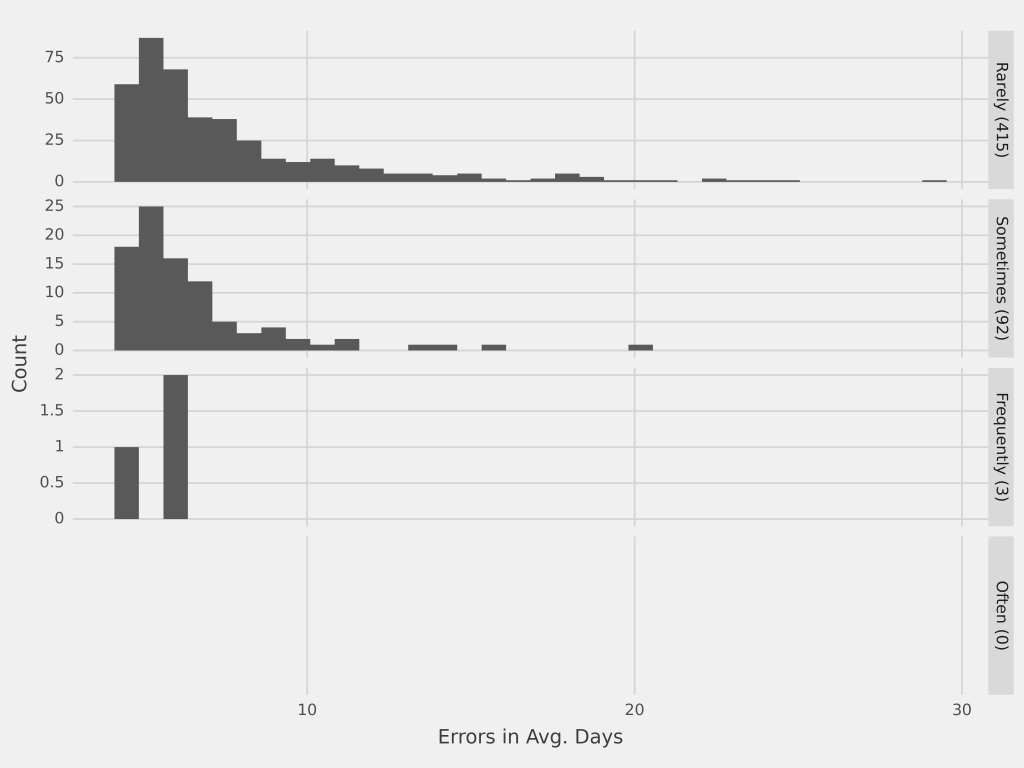

An order proposal contains several products from a single supplier, so it is necessary to evaluate how well the conclusion works as a whole. For this purpose, the mean absolute error obtained from backtesting is divided by the average number of units sold per day. This measurement shows the error in days, which is useful for finding weaknesses in the conclusion. It also provides information on how well the “out of stock” point shown in Figure 3 can be hit.

Figure 3 shows how well the entire product portfolio of the central warehouse can be forecast. The error is specified in average error days. To do this, the average absolute error is first calculated and then divided by the average units sold per day. By categorizing the products according to sales figures, the chart clearly shows that the system is very good at handling products that are sold frequently. At the same time, it is clear that rarely sold products are far more difficult to value. The analyses of simple and robust methods are often the best choice for rarely sold items.

The forecasts are equipped with additional safety precautions to increase accuracy and avoid excessive deviation from the realistic scenarios. The safety precautions consist of checking the quarters of the last few years and comparing whether the estimated demand is within a certain percentage range; if not, orders are limited within this range. These safety precautions help to prevent overstocking or understocking of products.

(a)

(b)

Figure 3: (a) shows the histogram of errors below the 95% quantile for all products. (b) shows the histogram of errors above the 95% quantile for all products. The error is given by the average number of days that the model estimate is off. This metric is useful for heuristics as it shows how well the “out of stock” point can be reached. The categories on the y-axis indicate how often a product is sold on average, including a count in brackets (number of products that fall into this category). The figure shows that the conclusion works well for frequently purchased products. However, there is room for improvement for products that are rarely sold.

Silent mail: Interaction between the components

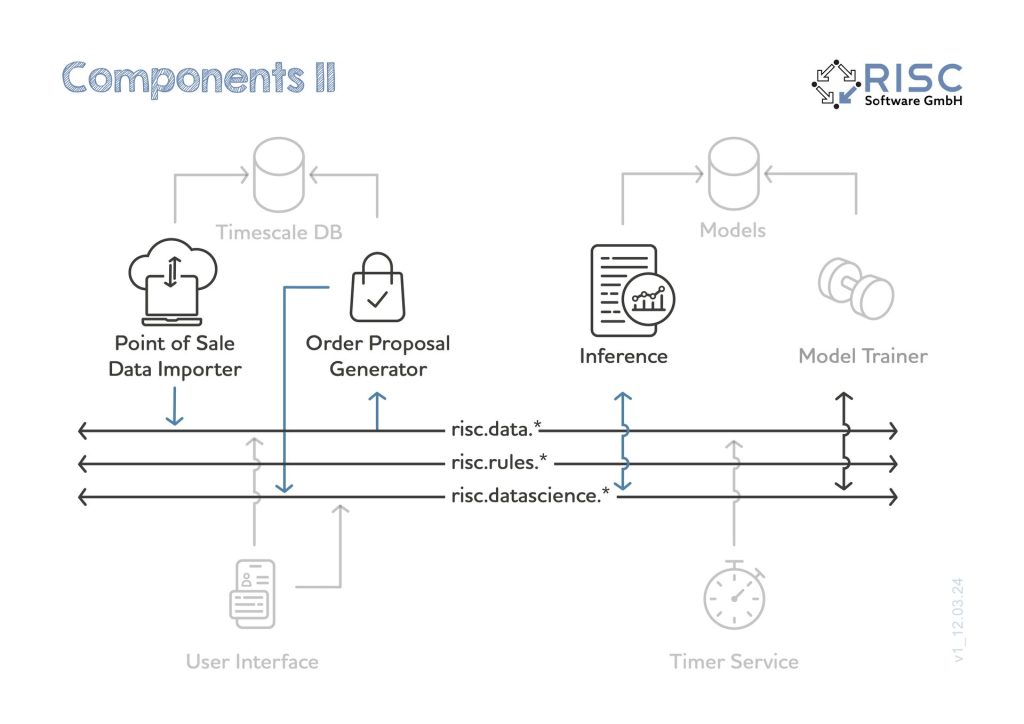

The smooth interaction of different software components plays a decisive role, especially when it comes to the integration of state-of-the-art software. A proven approach is to use a message bus to facilitate communication between the different parts of the system [7]. It can also be used to implement complex processes, with messages serving as triggers for specific actions or workflows. Figure 4 illustrates the order proposal generation process. This process is triggered by new data imports. The order proposal generator receives the messages sent by the import process and starts the inference process. The results are saved in the database and can be exported as CSV files to load the data into the retailer’s SAP system.

Figure 4: This figure shows all components of the system. They all interact with each other via messages. At the top left you can see the data import and the coordinator for generating order proposals. The training process and the inference are shown at the top right. The lower area shows how the user interface interacts with the data importer/exporter. Finally, there is a timer service that performs periodic tasks. The entire application is loosely structured into three components: Data, Rules and Data Science.

Conclusion: Over 50% effectiveness – automated order proposals transform the supply chain

In a comprehensive order proposal process, proposals are generated for 271 suppliers, whereby it is noteworthy that 56% of these proposals are accepted by the employees without any changes. Furthermore, ten suppliers are processed fully automatically by the system, which underlines the efficiency and accuracy of the process. In addition, around 10,000 products are analyzed and processed by a specially developed machine learning pipeline. Products that do not sell regularly still pose a particular challenge with this approach.

Qualitative findings from the project are also available. As the range of products managed by the system increases, reducing the training time required for the models becomes more important. It turns out that order proposals are frequently created for some suppliers due to their extensive product range. Acceptance of the system and the forecasts varies considerably among users, although improved transparency and traceability of the process and the models could potentially help to increase acceptance.

In conclusion, it can be said that the system makes a significant contribution to the process. At the same time, there are numerous opportunities to further improve and expand this process.

The results and methodology were presented at the ISM Conference 2023 in Lisbon, the corresponding article [8] is published in Procedia Computer Science 232C (2024) (DOI: 10.1016/j.procs.2024.01.176).

References

[1] J. Aastrup, H. Kotzab, Forty years of out-of-stock research – and shelves are still empty, The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 20 (2010) 147-164. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080%2F09593960903498284. doi:10.1080/ 09593960903498284.

[2] K. Q. Dadzie, E. Winston, Consumer response to stock-out in the online supply chain, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 37 (2007) 19-42. doi:10.1108/09600030710723309.

[3] S. Anand, S. Chadha, Out-of-stocks are more costly than losing a sale – but there’s a fix, https://www.supplychaindive.com/news/ reduce-retail-out-of-stocks-AT-Kearney/545439/, 2019. Accessed: 2023-03-29.

[4] W. Zinn, P. C. Liu, CONSUMER RESPONSE TO RETAIL STOCKOUTS, Journal of Business Logistics 22 (2001) 49-71.doi:10.1002/j.2158-1592.2001.tb00159.x.

[5] G. Ke, Q. Meng, T. Finley, T. Wang, W. Chen, W. Ma, Q. Ye, T.-Y. Liu, Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree, in: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, NIPS’17, Curran Associates Inc, Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017, p. 3149-3157.

[6] S. Makridakis, E. Spiliotis, V. Assimakopoulos, M5 accuracy competition: Results, findings, and conclusions, International Journal of Forecasting 38 (2022) 1346-1364. doi:10.1016/j.ijforecast.11.013.

[7] P.Kannisto,D.Ha ̈stbacka,T.Gutie ́rrez,O.Suominen,M.Vilkko,P.Craamer, Plant-wide interoperability and decoupled, data-driven process control with message bus communication, Journal of Industrial Information Integration 26 (2022) 100253. doi:10.1016/j.jii.2021.100253.

[8] Falkner, D., Bögl, M., Gattinger, A., Stainko, R., Zenisek, J., & Affenzeller, M. (2024). Integrating machine learning into supply chain management: Challenges and opportunities. Procedia Computer Science, 232, 1779-1788. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2024.01.176

Ansprechperson

Author

Dominik Falkner, MSc

Data Scientist