Anomaly detection in industrial image data

Why standard AI fails in production reality – and specialized approaches make the difference.

by Patrick Kraus-Füreder and Markus Steindl

AI enables new forms of automated quality assurance – with enormous potential, but also practical hurdles in terms of data availability, model architecture and system integration.

Contents

- Between everyday life and industry: why generic AI fails

- Image anomalies: Visual conspicuousness vs. semantic error

- Supervised or unsupervised?

- Labeled data: The bottleneck of practice

- Variability as a reality – and a challenge

- Adaptivity as the key to the future

- Hardware requirements in live operation

- RISC as a solution partner: from model architecture to operational implementation

- Conclusion

- Six questions that companies should ask themselves before using anomaly detection

- Contact us

- Authors

- Read more

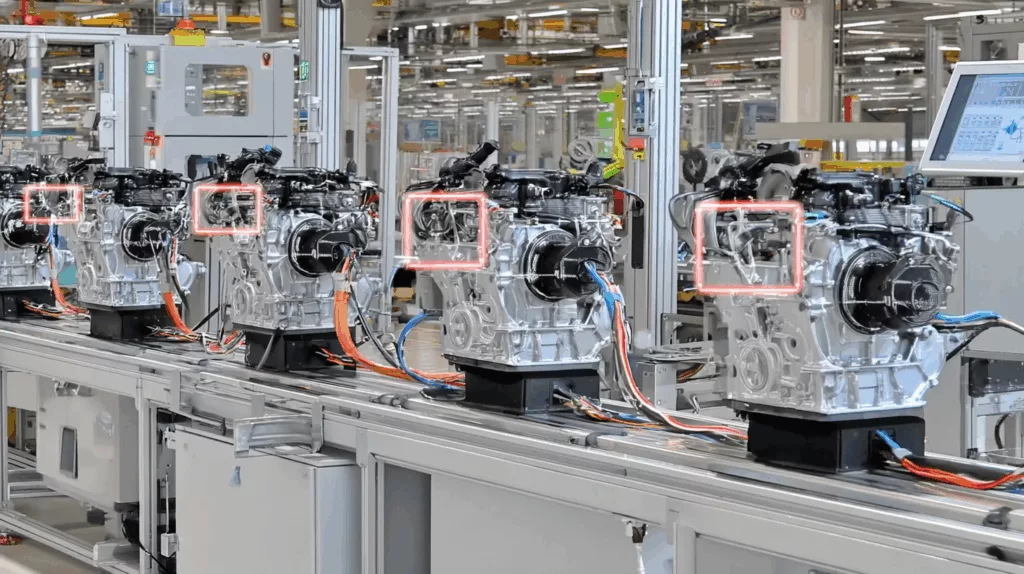

Between everyday life and industry: why generic AI fails

Most pre-trained computer vision models from the open source sector or from research institutions are based on image databases such as ImageNet, COCO or OpenImages. These contain millions of images, but almost exclusively from everyday contexts – such as cars, people, animals or pieces of furniture. Specific industrial scenarios, such as those that occur in manufacturing, are hardly represented in them, if at all, and can therefore only be depicted inadequately. This data is therefore only of limited use in industrial production.

As a result, a model that reliably distinguishes between cats and dogs often fails completely when it is supposed to assess the quality of a plug connection or detect fine cracks on a highly reflective metal surface. The visual features that define industrial anomalies are simply different – often more subtle, specific and context-dependent.

Figure 1: Examples of industrial anomalies on metallic fasteners (drive-in nuts). Left: Original images, right: marked damaged areas. Such subtle, context-dependent defects cannot be adequately captured by generically pre-trained AI models.

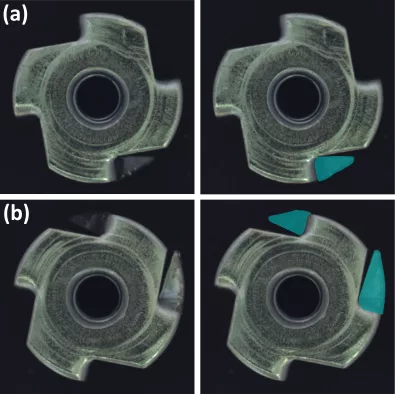

Image anomalies: Visual conspicuousness vs. semantic error

Anomalies in industrial image data are not only rare – they also take many forms. They can be roughly divided into two classes:

- Structural anomalies: These are local, usually texture- or pixel-based deviations that are “new” in their characteristic patterns compared to the training data. Typical examples are scratches, dents, cracks or soiling on surfaces. Detection is carried out, for example, by comparing sections or feature memory networks that mark unknown textures or shapes as anomalous.

- Logical anomalies: These anomalies violate the semantic or spatial rules that were learned from correct images without individual objects being technically defective. Examples are missing or additional components, incorrect placement, incorrect arrangement or deviating number of expected components. Their detection requires an understanding of global object relationships and counters, for example through autoencoders or hybrid models that check both local and logical constraints.

A robust anomaly detection system must be able to deal with both types of error – and must not rely on rigid reference images or simple differences. It needs contextual knowledge and the ability to interpret “meaning”, not just “deviation”.

Figure 2: Example of different classes of industrial anomalies. (a) Structural anomaly: the wire is damaged or broken. (b) Logical anomaly: instead of a single wire, there are two faultlessly laid wires. While the former is visible locally, the latter violates the semantic expectation of the correct component configuration.

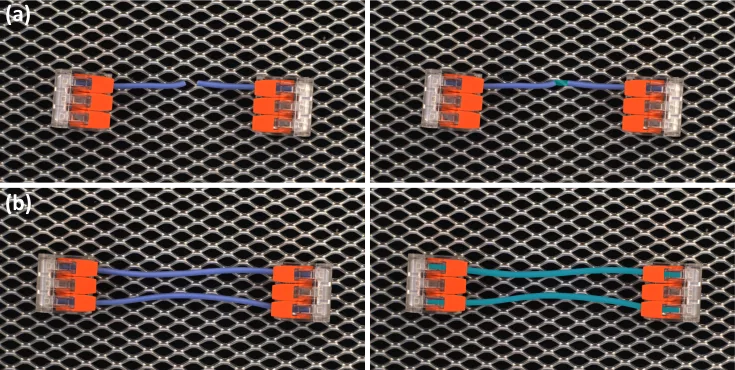

Supervised or unsupervised?

A common assumption: in order to reliably detect anomalies, a model needs as many fault examples as possible. In industrial reality, however, the opposite is the case: errors should occur as rarely as possible – ideally not at all. And this is precisely why they are usually almost completely absent from the available data sets.

This is a significant problem for classic supervised procedures. Without sufficient fault examples, they cannot draw any meaningful dividing lines between good and bad. Instead, modern industrial applications rely on unsupervised or one-class learning methods in which only good images are used for training. The model learns the characteristics of “normality” – and recognizes anything that deviates significantly from this as potentially anomalous.

Although these procedures do not require explicit error data, they do have other requirements: The definition of what is considered “normal” must be clear and consistent. In addition, typical production-related deviations – such as slight changes in position, surface variations or different exposures – must be sufficiently represented in the training data set so that the system does not incorrectly interpret them as defects.

Only if the real variance of everyday production is represented in the “normal picture” can the system act robustly in the face of real fluctuations.

Figure 3: A complete annotation of all potential production errors is hardly possible in practice. Instead, the “normal” can be learned unsupervised and deviations can then be recognized as potential anomalies.

Labeled data: The bottleneck of practice

Even if error images were available, their annotation is expensive and time-consuming. Their targeted generation is often impractical: production lines have to be stopped, errors deliberately provoked and then rectified manually – a time-consuming and expensive process that is rarely justified.

In addition, even in very large production data sets, real errors have often simply not yet occurred. This is not a verification problem, but a desirable state – after all, industrial quality assurance aims to avoid errors at an early stage. For the training of a model, however, this means that there are no concrete examples of anomalies that must nevertheless be detected in the future. This means that the existing labeled defect data – if available – is often incomplete and not representative of the entire range of potential deviations.

Unsupervised methods offer a viable approach here: they do not require explicit fault images, but learn exclusively from fault-free examples. In many industrial scenarios, they are therefore the only realistic option – provided that the quality and consistency of the good images is high and the model architecture allows a distinction to be made between tolerable variance and genuine anomalies.

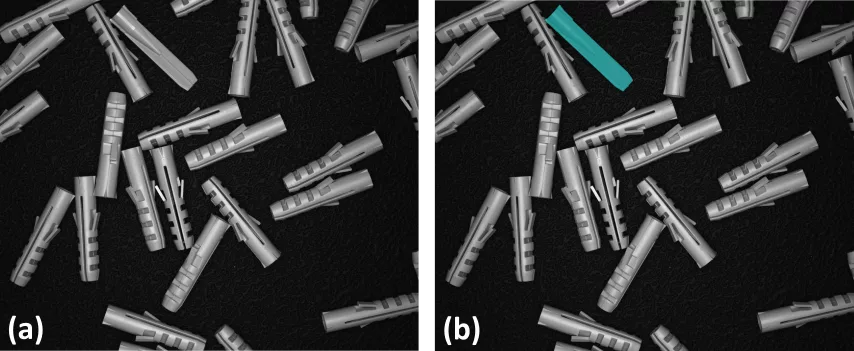

Variability as a reality – and a challenge

Industrial image data is rarely homogeneous. Even with consistent processes, they are subject to natural variance – due to:

- Variable-position components such as connection cables, hydraulic lines or hoses

- Changing lighting conditions due to ambient light, machine shadows or seasonal influences

- Scattering on surfaces due to manufacturing tolerances, contamination or assembly marks

These factors mean that two “correct” images often differ significantly from each other – even though both are error-free. A system that is too sensitive constantly reports false alarms. A system that is too coarse overlooks real problems. The fine line between sensitivity and robustness is the central challenge of industrial anomaly detection.

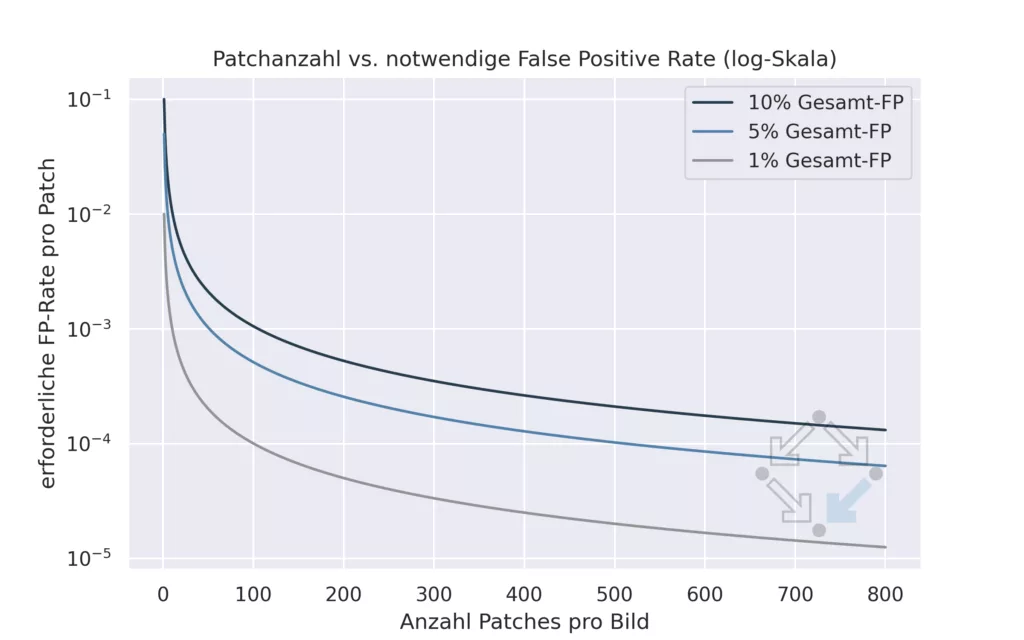

It becomes particularly critical with high-resolution images: As potential anomalies can occur anywhere, many methods work on 256×256 pixel sections. To examine a detailed image of 2048×2048 px, for example, hundreds of these sections are required.

The problem is that each section is a separate “test”. And the more tests are carried out, the higher the probability of false-positive results – even with good individual performance. This statistical accumulation problem is an often underestimated source of errors and frustration in practice.

Figure 4: Patch-based anomaly detection requires extremely reliable detection of individual errors. With 500 patches per image, the misclassification rate per patch must not exceed 1 in 10,000 in order not to exceed a false positive rate of 5% per image.

Adaptivity as the key to the future

Even a well-trained, finely tuned system loses its effectiveness when reality changes. New suppliers, modified components, updates to the product design – they all change the visual appearance of the normal state.

A system that cannot react to this will either report everything as an error – or nothing at all. Modern anomaly detection must therefore be adaptive and capable of learning. The aim is to integrate new “normal states” with a small amount of sample data without having to completely retrain the model. Methods from the field of few-shot learning or continuous learning are becoming increasingly relevant here.

Hardware requirements in live operation

One aspect that is often underestimated is the technical requirements of an anomaly detection system in live operation.

Although many modern computer vision models are considered comparatively efficient in inference, in practice specialized hardware resources are required to work reliably and in real time.

- Powerful CPUs are necessary for image pre-processing: cropping, color space conversion, contrast adjustment and other processing steps must be carried out for each image – often under time pressure and parallel to the running line.

- Graphics cards (GPUs) offer the decisive speed advantage in the actual image evaluation (i.e. the AI inference step) – especially with high-resolution images or complex models.

Whether the hardware is installed directly on the line (e.g. in an edge device) or operated centrally (e.g. with a camera connection to a computer server) depends on the scenario in question. The important thing is that these requirements should already be taken into account in the planning phase.

This is the only way to prevent a working prototype from failing later due to excessive response times or system overload.

RISC Software as a solution partner: From model architecture to operational implementation

The implementation of industrial anomaly detection requires more than simply applying ready-made models. Each application scenario has its own requirements: different image qualities, product variants, cycle times or integration environments. Standard models often reach their limits here – whether in terms of robustness, scalability or dealing with variable reality.

RISC Software GmbH sees itself as a solution partner that does not shy away from this complexity: we analyze the specific use case, adapt existing model architectures in a targeted manner – and integrate them into functioning systems. From image acquisition to production-related decisions, we help companies not only to test AI-based quality control, but also to make it sustainable and productive.

Conclusion

Anomaly detection is not a finished product, but a continuous process. Anyone who takes the reality of industrial image data seriously – with its variance, imbalance and permanent change – can use AI-based quality control sensibly and effectively. This requires suitable models, realistic expectations and an agile concept for operation and further development.

Six questions that companies should ask themselves before using anomaly detection

Werden Bilder in gleichbleibender Qualität erzeugt?

Anomalieerkennung lebt von Konsistenz. Unterschiede bei Kameraposition, Beleuchtung oder Hintergrund führen schnell zu Fehlalarmen. Nur wenn die Bildaufnahme technisch stabil und wiederholbar ist, kann KI sinnvoll eingesetzt werden.

Gibt es genug Beispielbilder für den Normalzustand?

Auch wenn keine Fehlerdaten vorhanden sind: Ein gutes Anomalieerkennungsmodell braucht viele Bilder von fehlerfreien Produkten. Je größer und vielfältiger dieses Set, desto robuster kann das System später reagieren.

Sind bekannte Fehlerarten dokumentiert – auch mit Bildbeispielen?

Fehlerbilder mögen beim Training teilweise nicht nötig sein, sind aber essentiell bei der Bewertung des fertigen Systems. Nur wenn klar ist, welche Anomalien erkannt werden sollen, lässt sich die Leistungsfähigkeit objektiv beurteilen.

Wie oft ändern sich Bauteile, Lieferanten oder Produktvarianten?

Ein KI-System erkennt, was es kennt. Wenn sich das Aussehen von Bauteilen regelmäßig ändert, braucht das System die Fähigkeit zur schnellen Anpassung – und das Projekt muss so konzipiert sein, dass solche Anpassungen eingeplant sind.

Wer kann im Unternehmen beurteilen, ob ein gemeldeter Fehler tatsächlich einer ist?

Kein System ist perfekt. Es wird Grenzfälle geben. Wichtig ist, dass intern eine Ansprechperson (z. B. aus der Qualitätssicherung) definiert ist, die Rückmeldungen geben kann – damit das System laufend besser wird.

Gibt es geeignete Hardware für den Live-Betrieb?

Für Tests reicht oft der Laptop – für den produktiven Einsatz braucht es zuverlässige Bildverarbeitung in Echtzeit. Das erfordert leistungsfähige CPU-Ressourcen und meist auch eine GPU – direkt an der Linie oder im Netzwerk.

Contact us

Authors

DI Dr. Patrick Kraus-Füreder, BSc

AI Product Manager

DI Dr. Markus Steindl

Senior Data Scientist